Here’s a common problem: we love to keep score, but only as long as we’re winning! When we’re not – well, we don’t really want anyone to see the report card. But in order to double your value and make change happen, we need to shift our mindset.

As Dell founder Michael Dell says, “We spend a great deal of time and energy in setting the right goals and finding the right ways to measure them.”

Big or small, Dell scrutinizes relevant details of what they do like crime scene investigators, “to see what makes a difference to customers.”

Dell pays close attention to the evidence and refuses to be misled by “the things that we think are great because people ought to like it.”

I chatted with Dell when we were at Davos some years ago, and as we walked through the slippery Swiss snow in hiking boots and business suits, he told me about a time when he, as a teen, struggled with his paper route. It was “going nowhere” as a money-making venture until he noticed that people tend to buy a lot of new things – like newspaper subscriptions – when they have major changes in their lives – like moving into a new community, changing homes, having kids, getting married, etc.

This observation yielded a breakthrough idea: focus on life events and changes among the customers he served. He tracked that data and fulfilled their unique needs at various stages of their lives.

Whereas most kids would’ve viewed the job as a way to earn pocket money by tossing papers onto lawns, Dell completely doubled the value of his venture. Not only did it change the nature of his paper route, generating $18,000 to buy a BMW in high school when his peers were still asking for allowance money, but this early observation in mapping customer data would give him insight into buying habits for the computer business he’d go on to found.

buy a BMW in high school when his peers were still asking for allowance money, but this early observation in mapping customer data would give him insight into buying habits for the computer business he’d go on to found.

“I would characterize the start up of the company as a series of experiments,” Dell said, pointing to the white board where he had a list of noble ideas that missed the mark. “Most of these failed, but none of them were large enough disasters to destroy the company.”

Most people don’t do well with ambiguity, believing it the enemy of audacity and innovation. It strikes fear in our heart and puts doubt in our heads. When was the last time you were able to sell an idea to your boss, your partner or your team without an exact battle plan for getting it done? Did they not want a detailed process for getting there, and certainty about the outcome?

It’s human nature to crave certainty and repudiate ideas that don’t have guarantees. And yet, very few things do. Great ideas and great careers don’t have it all figured out before they launch.

This was exactly the case for Michael Dell and his desire to create and double value in the computer industry. His plan was clear and confident, with a paucity of detail or certainty. But that is not how it looks when you read about Dell. The press gushes over him as if he found a chest hidden in his freshman dorm room containing the treasure map for his life.

If you’ve met Michael, however, he is a self-effacing, down-to-earth guy who reassures you that he had no precise plan. He just dared to go  where no one had gone before. The compelling nature of the goal, not the plan, is what launches entrepreneurs.

where no one had gone before. The compelling nature of the goal, not the plan, is what launches entrepreneurs.

Dell realized he could create more value in the computer industry by bypassing retail stores and selling his computers to consumers direct by mail. He got almost instant validation, netting a cool $80,000 in his first year. Not surprisingly, he opted for selling computer equipment out of his bathtub at University of Texas, Austin, instead of getting a college degree.

In the time he would have taken to earn a sheepskin, he became the youngest person to take a company public on the stock market. But within a year, he faced disaster when his warehouses overflowed with excess inventory of electronic components. The enthusiasts’ package of computer technology he thought would sell bombed with consumers.

While Dell is known for his big idea about bypassing traditional retail stores, he desperately needed to clear inventory. It very nearly killed the company until he decided to distribute things through CompUSA and Best Buy stores for awhile, temporarily violating his original plan to sell only by mail.

No sooner did he get things back on track when the firm hit the wall again. Dell struggled with losses in a business that would prosper later – laptops – and he also faced costly mistakes in Europe. He was forced to cancel a second public offering to the stock market.

Clawing his way out of this  second big slump, Upside Magazine named Dell turnaround CEO of the year, and he delivered a line that has become legendary: “I hope I don’t ever win that award again!”

second big slump, Upside Magazine named Dell turnaround CEO of the year, and he delivered a line that has become legendary: “I hope I don’t ever win that award again!”

Responsible Chutzpah or Audacious Accountability

Like most people who double value in major ways, what Dell had going for him on this roller coaster ride was an odd mixture of Accountability AND Audacity. It’s tough to find the right word for this leadership quality. The Yiddish dictionary gets closer: We’re talking about a responsible form of chutzpah – the non-conformist gutsy audacity to create something despite all odds, for better or for worse. In this case responsible chutzpah leaves out the completely self-absorbed arrogance associated with the word.

Leo Rosten in The Joys of Yiddish defines chutzpah as “gall, brazen nerve, effrontery, incredible ‘guts,’ presumption plus arrogance such as no other word and no other language can do justice to. ”

The difference here is that those who continue to create and build value long-term are accountable – they are people who deliver for themselves and the outside world at the same time.

Accountability means: “to stand and be counted, as a part, a cause, an agent, or a source of an event or set of circumstances.” Audacious Accountability means you consider your life from the point of view that how it goes and what happens is up to you. Don’t worry; this is not an infomercial for so-called human potential movement psychobabble. This is one of best lessons from human history: You may or may not be to blame for what happens to you, but either way you are responsible for doing something about it.

Those who make big things happen time and time again don’t claim to feel in total control, but they do have the audacity to embrace the idea that they alone (or with the help of a Creator) are building their life for a reason, rather than life being something that happens to them while they’re making other plans.

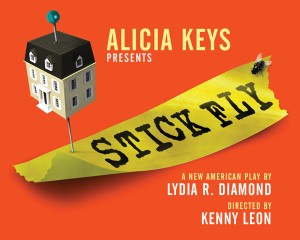

play the C chord,’ and I put my fingers down to play the C chord and I couldn’t tell the difference.”

play the C chord,’ and I put my fingers down to play the C chord and I couldn’t tell the difference.” and it won a Grammy. He’s since been nominated for another. It’s not far off from the 40 years he’d told himself as a teenager it would take to learn how to play.

and it won a Grammy. He’s since been nominated for another. It’s not far off from the 40 years he’d told himself as a teenager it would take to learn how to play.

that medical doctors at the time warned would cause heart attacks, hemorrhoids and even impotence: it was called daily exercise.

that medical doctors at the time warned would cause heart attacks, hemorrhoids and even impotence: it was called daily exercise. Yet when I met him, LaLanne still claimed to hate exercise! He said he couldn’t “wait until it [was] over every day,” but knew that he’d be “miserable if [he] didn’t do it,” he said. So why did he?

Yet when I met him, LaLanne still claimed to hate exercise! He said he couldn’t “wait until it [was] over every day,” but knew that he’d be “miserable if [he] didn’t do it,” he said. So why did he?

buy a BMW in high school when his peers were still asking for allowance money, but this early observation in mapping customer data would give him insight into buying habits for the computer business he’d go on to found.

buy a BMW in high school when his peers were still asking for allowance money, but this early observation in mapping customer data would give him insight into buying habits for the computer business he’d go on to found. where no one had gone before. The compelling nature of the goal, not the plan, is what launches entrepreneurs.

where no one had gone before. The compelling nature of the goal, not the plan, is what launches entrepreneurs. second big slump,

second big slump,